Sponges

Sponges are very unusual organisms. They belong to the animal kingdom, but in some respects they are more like plants, for example they are sessile (attached to the substrate), their shape is not symmetrical and they grow irregularly like a plant. Furthermore, they do not (or hardly) react to external stimuli and do not (or hardly) move. Sponges are multicellular animals. Each sponge is a single organism (not a colony as for example in the sometimes similar corals). Like all true multicellular organisms, sponges have different cell types that specialise in different functions. However, they do not have organs, and they completely lack some important cell types found in all other animals, such as nerve, sensory and muscle cells. Because of their simple structure, they are sometimes called Parazoa and set apart from all other multicellular animals, the Eumetazoa. But their simplicity actually makes them only more interesting: how do they manage to adapt to their environment and “function”?

Here you can skip the introduction and go directly to the species.

Sponges do not have true cell tissue, rather their cells lie embedded in a gel-like substance, the mesohyl. The cells of the sponges can be divided into three types: pinacocytes, choanocytes and amoeboid cells. The pinacocytes form the outer layer of the sponge as well as the base with which the sponge adheres to the ground, and they line the larger channels in the interior. The flagellate choanocytes line the interior of the sponge and generate the water flow through its body. The cells of the last type, the amoeboid cells, are not fixed in a place but can move around in the gel-like substance, the mesohyl. There are different types of amoeboid cells: the undifferentiated archaeocytes, from which all other cell types originate, the amoebocytes, which digest and transport the food in the sponge, the sclerocytes and spongocytes, which form the characteristic, species-specific skeleton consisting of spongin (horn) or of silica or calcium carbonate needles, and finally, the sex cells are also considered amoeboid cells.

Sponges feed by filtering seawater. They are active filter feeders, i.e. they generate the water flow that streams through their body. The outer layer of the sponge is perforated by numerous small pores through which water is absorbed into the sponge where it flows through a system of chambers connected by channels, which are lined with choanocytes. The water flow is generated by the choanocytes beating their flagella in a coordinated manner. Around the flagella lies a ring of mucus-covered contractile microvilli to which food particles adhere. The food particles are transported to the cell surface and absorbed there by phagocytosis. In this way, the sponge can absorb particles ranging in size from 1 to 10 µm, but not organic substances dissolved in the water. The choanocytes pass the food on to other cells. Unusable particles and substances are released and transported away with the outflowing water. The water is discharged from the sponge through one or more larger, usually slightly elevated outflow openings (osculi). It is usually actively ejected so that it is not immediately taken back up through the pores. Gas exchange in the sponge takes place across the entire outer and inner surface.

The kidney sponge has many large water outlets (osculi). The pores through which the water is absorbed are too small to be seen with the naked eye.

Although sponges have neither sensory organs nor nerve cells, they can perceive various stimuli and respond to them. Signals are transmitted both chemically and electrically. Numerous neurotransmitter substances which are also used by higher animals have been detected in sponges. Some pinacocytes possess actin filaments, which they use to perform contractile movements that regulate the sponge’s water supply. It has been found that some sponges can even move slowly (e.g. Thetya), although it is still unknown how this movement is managed.

The “skeleton” of the sponges consists of a more or less rigid structure of calcite (calcareous sponges), silica (siliceous or glass sponges) or an organic substance, the collagen-like spongin, which is used together with silica in most of the sponges, the demosponges. The size and shape of the tiny skeleton parts, which can be fibrous, needle-like or star-shaped, for example, are characteristic of each species and therefore important for identification. The well-known bath sponges belong to the demosponges; they do not have hard needles, but their ‘skeleton’ is made up of fibrous spongin. Bath sponges also occur around Naxos, but rarely and only at greater depths.

After big storms one may find the skeletons of sponges, that were torn off by the waves.

Here you can see the fine structure of a sponge skeleton.

Sponges reproduce either asexually through budding or colony formation, or sexually. In sexual reproduction, either the sperm and eggs are released freely into the sea water, or the eggs remain in the sponge and are fertilised there. In both cases, there is a free-swimming larval stage, which attaches itself to the substrate after one to three days. Under very unfavourable environmental conditions, the entire sponge can disintegrate into small fragments, from each of which a whole new sponge can sprout – or they reinhabit their former skeleton.

Sponges are eaten only by very few animals. Most species possess repellent substances that prevent other organisms from growing on them. The only animals that actually feed on sponges are certain species of nudibranchs, which often spend their entire lives on the sponges. However, many animal species (brittle stars, feather stars, worms, etc.) live in the cavities of sponges without harming them. Some species of sponge form symbiotic relationships with single-celled algae, and all contain bacteria that often also have a symbiotic relationship with the sponge. It is thought that the bacteria may supply the sponge with organic substances that they absorb from the water. It is also possible that various organic substances are produced by the bacteria in the sponge. The biomass of the microorganisms in the sponge can amount to half its weight. In principle, sponges can continue to grow indefinitely and live to any age. For sponges in the Southern Ocean, individual specimens have been calculated to be 10,000 years old, which probably makes them the oldest living organisms on Earth.

Sponges form their own phylum (Porifera), which comprises about 7,500 species. Some of these live in fresh water, but the vast majority live in the sea. They are divided into three classes: calcareous sponges (Calcarea), demosponges or common sponges (Demospongiae) and glass sponges (Hexactinellida). Around 600 species have been identified in the Mediterranean; they occur from the water surface to great depths and grow on the sea floor, on rock faces and in caves or grottos. Almost all of the species described here belong to the demosponges; only the the last species belongs to the Calcarea.

sponge species on Naxos

Sponges on Naxos

The Photo gallery of the marine animals provides an overview of the described species.

A note on identification: Unfortunately, identifying sponges from photographs is only possible to a limited extent. To be certain of the species, one would have to examine the skeleton needles of the sponge, but I have spared myself and the sponges this process so far. I hope and believe that presenting the species is valuable, even if the identifications may be wrong.

Here you can jump directly to the species (return with the back arrow or by swiping back):

Stony sponge, Petrosia ficiformis – Scalarispongia scalaris ? – Kidney sponge, Chondrosia reniformis – Geodia spec. – Spirastrella cunctatrix ? – Crater sponge, Hemimycale columella – Orange puffball sponge, Tethya aurantium – Yellow boring sponge, Cliona – Ascandra

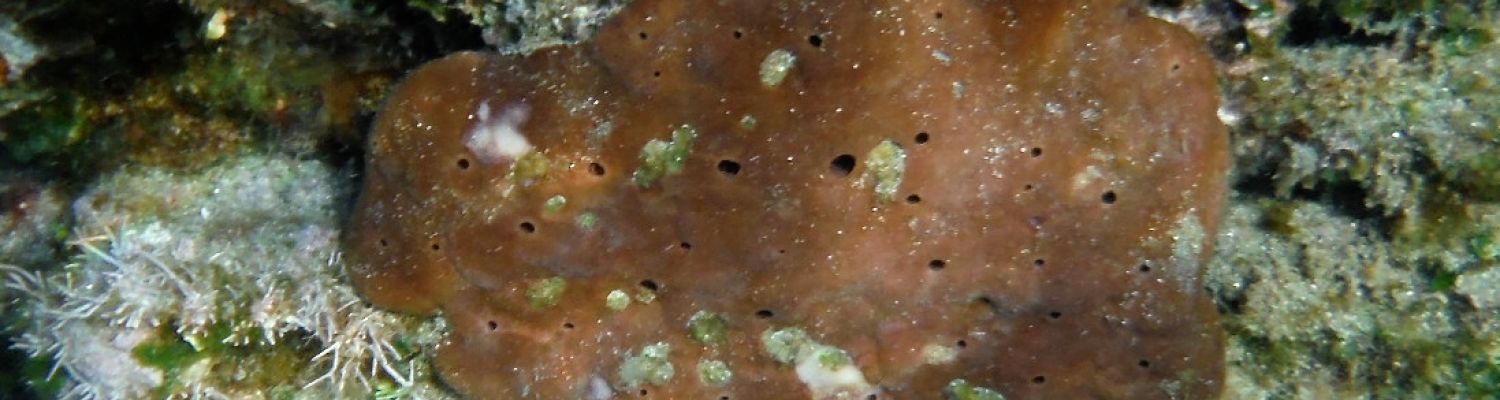

Stony sponge, Petrosia ficiformis, Poiret

The stony sponge is quite common in shallow waters. Often one may see the beautiful dotted sea slug on it (unfortunately, I don’t have a photo).

The stone sponge forms a thick, brown body with a smooth surface and many evenly distributed outflow openings.

Scalarispongia scalaris ?, Schmidt

This species has a black colour and shows numerous small cones on its surface. The osculi of this species are rather small.

Scalarispongia scalaris is very common in shallow water. Characteristic are the cone-like papillae on the surface.

a small individual

The sea slug Felimare tricolor feeds on sponges of the genus Scalarispongia.

Kidney sponge, Chondrosia reniformis, Nardo

The kidney sponge forms large colonies of irregularly curved, thick, often kidney-shaped individuals, each of with has several protruding osculi. The sponge body is marbled with light and dark brown colours. The kidney sponge possesses no mineral skeletal elements; the skeleton consists only of spongin. The kidney sponge is quite common in shallow water, especially on slightly overhanging rock faces.

The kidney sponge is common in shallow water.

It can be recognised by its characteristic shape and marbled colouring.

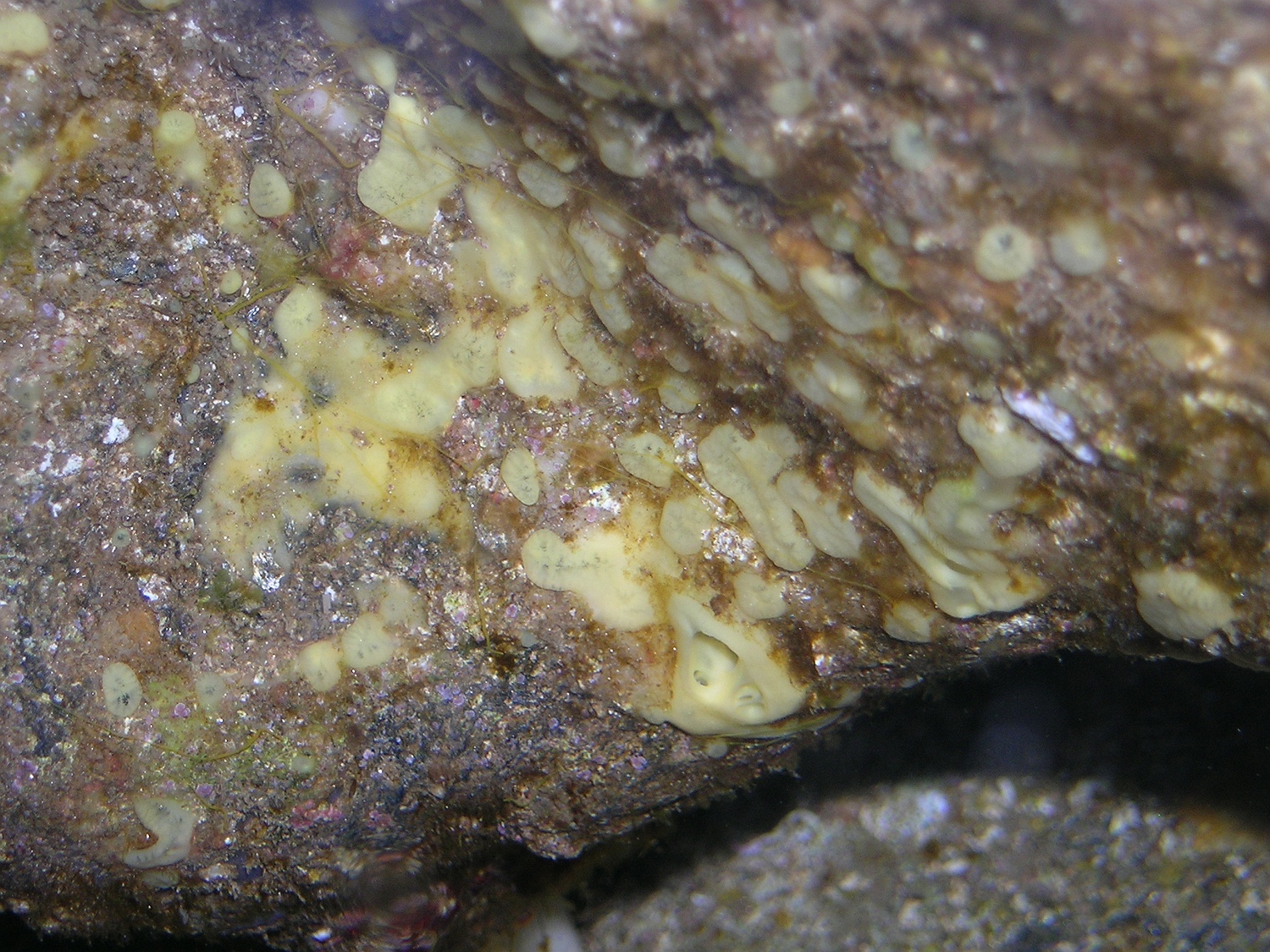

Geodia spec.

The genus Geodia is rather common, but easily overlooked because the surface of these sponges is usually covered with sediment and sometimes also overgrown, so that they do not stand out much. Characteristic for Geodia are the numerous small needles of silicic acid on their surface; it is best not to touch them. They are usually more or less spherical in shape, often with a large indentation in the middle; the colour of the sponge (as far as can be seen) is light yellow. Several species occur in the Mediterranean, which can only be distinguished by the shape of their needles.

Small individual of Geodia; you can see the typical round shape and yellowish colouring.

Sponges of the genus Geodia are always covered with sediment that is captured by the protruding silica needles on the surface; in addition, they are usually at least partially overgrown by other organisms.

Older individuals often take on a more irregular shape.

Spirastrella cunctatrix ?, Schmidt

This beautiful species can be found in very shallow water, but usually in the shade of overhanging rocks. It grows in a crust-like form and shows characteristic translucent channels that run radially towards the outflow openings. However, several other species are very similar; for a correct identification one would have to examine the skeletal elements.

Spirastrella cunctatrix is bright orange in colour and shows characteristic radial channels surround the large osculi.

This species often grows in small cavities or under overhanging rocks.

A number of sponge species form orange-coloured crusts; reliable identification by a photo is not possible.

Crater sponge, Hemimycale columella, Bowerbank

The crater sponge is rather rare in our area. It has a brownish colour and is densely covered by crater-like pits.

The crater sponge can be recognised by the crater-like pits that densely cover its surface. The protruding osculus can be seen in the lower part of the sponge.

Orange puffball sponge, Tethya aurantium, Pallas

The Orange puffball sponge resembles an orange not only in shape and colour, but also in its internal structure. Its interior contains radially arranged silica crystal needles which the sponge uses to conduct light into its interior, as if by fiber optic cable. There the light is used by symbiotic algae for photosynthesis – an astonishing example of a ‘biotechnological invention’ that nature developed millions of years before humans, even in an organism as simple as a sponge.

The Orange puffball sponge lives up to its name. It forms a small, orange-coloured ball with a slightly rough surface. The protruding osculus is clearly visible in this specimen.

The rather rare Orange puffball sponge grows in shallow water.

Yellow boring sponge, Cliona celata, Grant

Some sponges, known as boring sponges, live in rock, always in limestone, into which they etch small cavities. Little of the sponge is visible from the outside; usually, only small yellow (or orange) rims around the holes can be seen. In the Mediterranean Sea 20 species of the genus Cliona have been found, some of which are almost indistinguishable in appearance. Cliona celata is the most common species. Although inconspicuous, it is very common on marble in the coastal area. Because it erodes the rock, this species plays an important role in shaping the coastline; in addition, many other organisms also find a foothold on or live in the perforated rocks it leaves behind. In addition to calcareous rock, boring sponges also live in mussel shells (sometimes causing considerable damage to mussel farms) and corals. The yellow boring sponge may also occur in a epilithic form. Borings sponges belong to the demosponges.

From the holes in the stone protrude yellow small rims of the endolithic sponge.

yello boring sponge, here with very densely standing openings

This yellow boring sponge grows in a form that is not wholly endolithic.

The boring sponge is extremely effective at ‘mining’ the rock. It accomplishes this in an astonishing way using special etching cells which can freely move to where they are needed. The etching cell drives tiny filopodia of a diameter of 0.5 µm into the rock from its edges, using acid and enzymes to dissolve the limestone. These filopodia turn inwards beneath the etching cell. In this way, a chip of rock of about 50 µm length is separated and detached as a whole. The chip is ingested by the etching cell and both the cell and the chip are carried away by the outflowing water. In this way, only about 2% of the rock needs to be chemically dissolved; the rest is physically chipped off. The sponge thus quickly and effectively creates small chambers in the rock, connected to each other by pores, in which it lives.

On marble beaches, you often find stones like this, which were once inhabited by a boring sponge. On the right-hand side, you can see the intact surface of the stone with the small holes from which the openings of the sponge protruded. On the left-hand side, the surface of the stone has been eroded away, revealing the chambers in which the sponge lived (similar to the chambers inside a “normal” sponge body).

Cliona rhodensis ?, Rützler & Bromley

Quite a few species of boring sponges occur the Mediterranean Sea. This orange-red specimen could belong to the species Cliona rhodensis, which was first described in the 1980s and is one of the most common boring sponge species around Rhodes. However, the species is not always accepted.

Cliona rhodensis (named after the island of Rhodes) is orange-red.

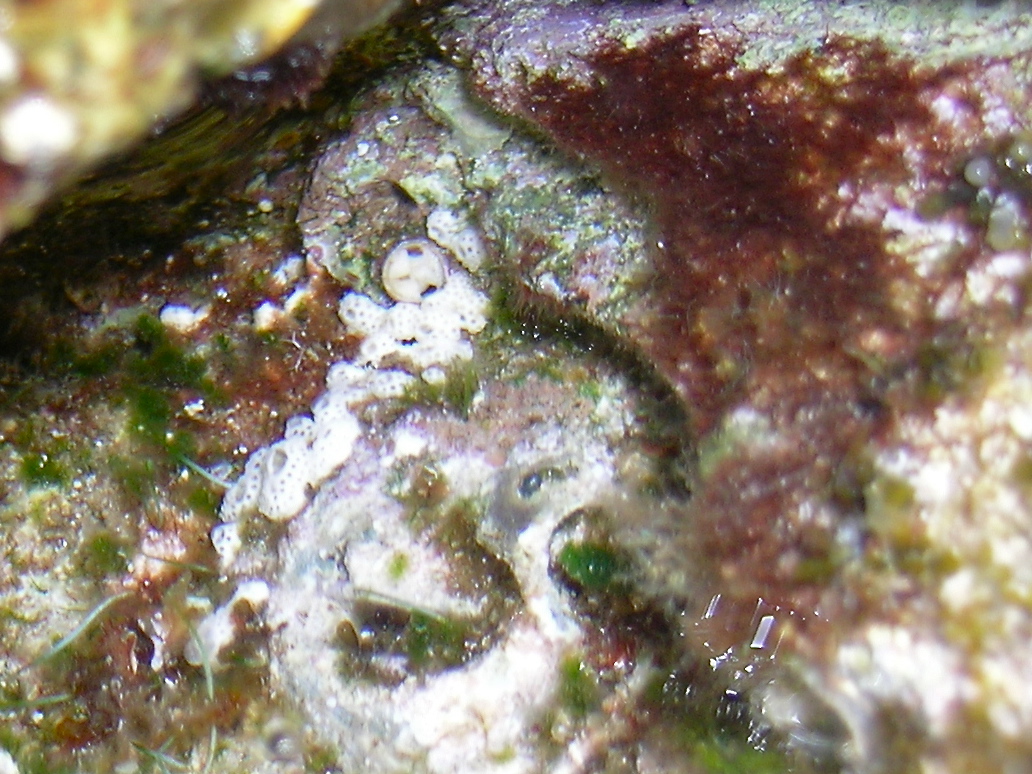

Ascandra contorta ?, Bowerbank

The calcareous sponges are characterised by their skeleton of calcium carbonate needles. They do not have a solid body, but consist of a network of fine tubes. Several species occur in the Mediterranean; this small white specimen could belong to Ascandra contorta or a related species.

This tiny sponge belongs to the calcareous sponges.

continue: Corals

back: Marine animals (Overview)

see also:

Much of the information in this article comes from this book: Robert Hofrichter (Hrsg): Das Mittelmeer, Fauna, Flora, Ökologie, Band II, 1: Bestimmungsführer